During last month’s obsession with Bluebeard, I discovered Bronte’s Jane Eyre and du Maurier’s Rebecca are considered ‘romanticised’ Bluebeard tales. I love Bluebeard (particularly Anglea Carter’s retelling, the Bloody Chamber) because it calls out violence (both within and external to us) as a warning to check behind locked doors and develop our intuitive insight.

I have worked in the community sector for some decades (it’s how I pay the bills) and at first, Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca left me cringing. But on further reflection, I realised I had undervalued the play of power dynamics between men and women, the rich and the less rich, the polite and the boorish in du Maurier’s novel. The problem is not the novel, the problem is billing the novel as a romance.

First, this is what I unequivocally enjoyed about Rebecca

It is a compelling read and I want to turn the page.

I was in Manderley; the sense of place is exquisite – I could smell the garden and the vases of flowers at every step of the plot.

The unnamed protagonist (and unreliable narrator) is well-developed and relatable. Oh dear, I remember being that insecure and unsure at her age.

Rebecca (the dead Mrs de Winter) is attractive as a character too. Maxim de Winter, not so much. This is where I struggled and now there are spoilers if you don’t want to know, skip to the end.

I was reeled into the mind of the new Mrs de Winter. Her jealousy of the dead Rebecca, her adolescent fantasizing, and her shyness. She is navigating her new world as the wife of Maxim and as a reader, I am gripped by the mystery of the secret that makes this a Bluebeard retelling. Maxim, her older husband is suitably gothic, tortured and emotionally remote.

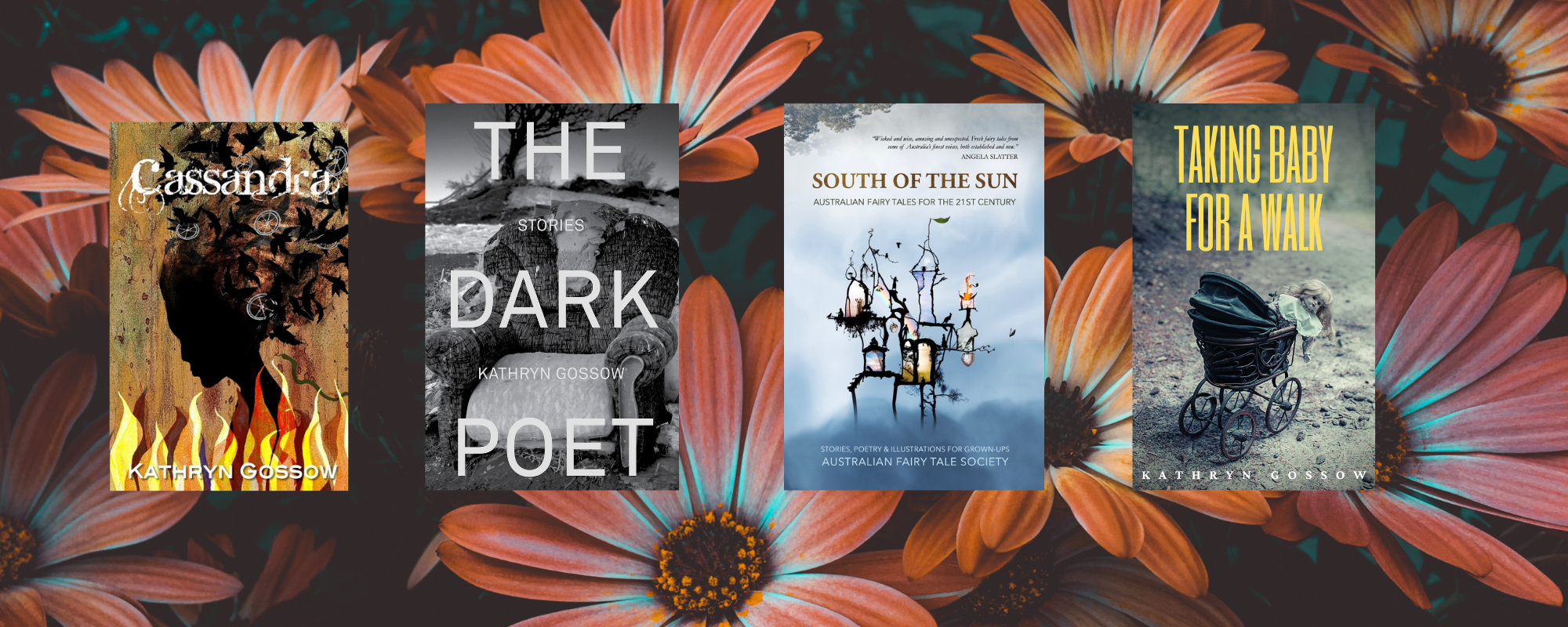

I know the allure of the Byronic gothic hero. I have been there in real life! I wrote a collection of short stories (The Dark Poet) to exorcise those demons.

The secret is revealed. Maxim murdered his first wife. The new Mrs de Winter becomes her husband’s accomplice in hiding the murder of Rebecca.

Ok, here is a tip. If your partner has killed his former partner, get the fuck out of there! There is nothing romantic about being his accomplice. This is a dangerous situation. This is the thing, Rebecca is not a great romantic novel and Maxim is not a romantic hero.

Rebecca’s ‘problem’ was she had other lovers. Max’s crime was a crime of passion. In Queensland, where I live, the partial defence of provocation was only amended in 2011, to “reduce the scope of the defence being available to those who kill out of sexual possessiveness or jealousy”

Rebecca is promiscuous and the new, unnamed Mrs de Winter is an innocent. One deserved to die and one deserves to live. I don’t feel the romance. Max de Winter is not alluring.

But, perhaps this is what du Maurier intended. She described the book as ‘rather macabre’. The de Winters do not get off scot-free. They lose their beloved home at the hands of Mrs Danvers. To me, she is the real hero of this book. She and Rebecca’s cousin, who advocates for her and accuses Max of murder. Unfortunately, he drinks too much and is boorish. This is also a crime. The de Winters are so polite and well-mannered

I found some commentary that claims a feminist spin on the new Mrs de Winter because she found her power and confidence as an accomplice. I can’t buy into that. Women who stand up and speak out about men’s violence fit my ideal of feminists, not those who hide the jealous crimes of passion men commit.

That’s how power works though. The second Mrs de Winter is young, has no money, no family, and no prospect of independence. The older, very wealthy Mr de Winter holds all the cards. Rebecca’s boorish cousin, her enamoured housekeeper Mrs Danvers, the boat builder, the legal system – even the fabulous Rebecca – none of them stands a chance against the wealthy patriarch of an ‘old’ connected family.

It took some searching for me to find Hitchcock’s 1940 movie Rebecca. Perhaps it says it all that Rebecca’s death was, though the result of Max’s violence, more accidental and audience palatable. The new wife’s decision could not be justified in the screen version if Maxim’s act was outright murder. But, as Daphne du Maurer intended, the novel Rebecca reeks with jealousy. It tilts with power imbalance and it will be a novel that will stay with me.

Kathryn……I saw Rebecca the movie as a very young teen. It terrified me and yet my mother couldn’t have been more glowing in her critique of it. I remember listening to her talking to her friends and thinking I must have been too young to “get it”. I’m going to revisit it with the book.

Terrified is a reasonable reaction! I hope you enjoy the book

This was my favourite book when I was eleven or so…

I wonder what appealed to you when you were 11. The drama?

The gothic nature of it all, I suppose. I was reading a lot of classics back then. Anna Karenina was another cherished favourite! I had this thing for Russian literature when I was a kid. Now, of course, I would probably read it with a more criticial eye, like you cover in your post. I do remember having feminist impressions about Anna Karenina (the character) back then, though–I just didn’t have anybody to talk books with, so it was pretty much all internal thought processes.

I am revisiting some of the classics I read when I was a teenager. I understand them much more now! In 20 years when I read them again, I will probably go even deeper. I don’t know how I would live without reading.