After reading Pride and Prejudice with the Pocket Bookclub I realised Pride and Prejudice was the Beauty and Beast story. I am no genius! Elizabeth Hopkins sets the plot similarities out rather succinctly at the Silver Petticoat Review or look at Kristen’s visuals in her post at See you in the Porridge .

Lizzie and Darcy don’t like each other, Darcy is a beast but eventually Lizzie learns Darcy is perhaps more socially awkward than rude and Darcy learns Lizzie is a witty conversationalist and can see past her dreadful family and they live happily ever after (except poor Lydia who marries a real beast – she is punished for being a flirt but that is a whole another post.)

Pride and Prejudice is a story about seeing past appearances. Just like the Beauty and the Beast. Right?

Stories get in our head. They become part of us and how we think. If we accept Beauty and the Beast as a romantic tale we forget its origins come from a time when women had fewer choices and we accept that romance can be manipulative and about power games where men are in control. We need to shed this cultural baggage.

First you need to know the Disney version is a bit different to the original fairy tale. Beauty and the Beast is not one of those anonymous tales handed down through generations. It was written by novelist Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve in 1740. It was then abridged and rewritten by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont in 1757 and her version is the more commonly known.

The annotated tale is at is at SurLaLane Fairy Tales to refresh your memory. This one is from to Andrew Lang is a bit of a mesh of both versions.

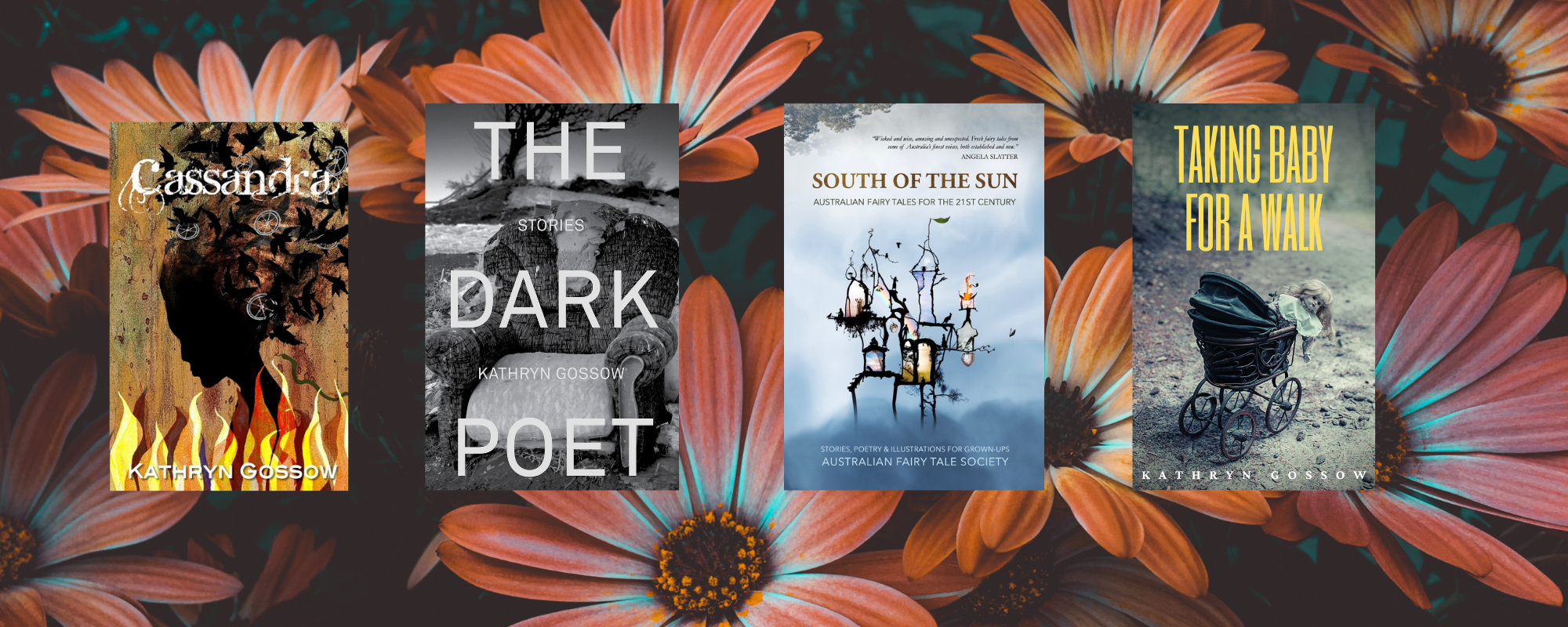

Translations of the first version are harder to find online but there is one in this book.

So the Beast’s behaviour. Let’s start with the Beast is damned stalky asking Beauty every night to marry him. His persistence is eventually rewarded with love and marriage (message to man – persist, persist, persist regardless of clear messages of no!). Let’s take this to the worst conclusion when no means maybe and women are assaulted – or give in to sex because he insists.

In the original De Villeneuve version, the Beast says “Will you sleep with me tonight?” There is no beating around the bush. He is persistently asking for sex and she is persistently saying no.

The Beast’s is emotionally manipulative – he says,

“Ah! Beauty, have you the heart to desert an unhappy Beast like this? What more do you want to make you happy? Is it because you hate me that you want to escape?”

Furthermore, he says, “If you don’t come back I will die.” I have had a broken boy make this very threat to me. He owned a gun. I liked him enough (at that point) to not want him to die. Beauty is responsible for the Beast’s happiness. She will, in fact, be punished if she fails. A woman should please her man. The happier you make him the nicer he will be. This is the trap of emotionally violent relationships.

The Beast gives Beauty everything she wants. Trunks and trunks of wonderful things to send back to her family. (He essentially buys her) She should be grateful for everything he gives her, right? I bought you dinner – be grateful and give me sex. Does that sound familiar?

Beauty is brave and cheerful. She sticks around and she forgives the Beast’s bad behaviour and the fact that he has imprisoned her. She does not challenge his bad behaviour. (The Beast says “I am satisfied with your submission”). Beauty is rewarded with a Prince. Message to women – be nice, be cheerful, be forgiving, don’t rock the boat and he will change. Message to man – roar, be frightful, no matter what you do, expect she will forgive you. Be a Beast.

Beauty’s father does not come off too well in the story either. He is willing to give up his daughter in exchange for his life. Her life is worthless than his. It is her role to sacrifice herself willingly. The message to young girls in the era of arranged marriages when this story was abducted by De Beaumont – to honour your parents and go with the man.Back to Jane Austen again and the mother’s concern that all her daughters marry well.

De Villeneuve’s Beauty and the Beast was a critique of a marriage system in which women had limited control. The man they were told to marry could well be a beast and they had no right to refuse him in the marriage bed and no property rights. At the time of writing, the Beast actually asking Beauty if she will go to bed with him was an indication that he was not really a Beast because a woman would have had no right to refuse the marriage bed.

In De Villeneuve’s tale, the emphasis is on the transformation of the Beast – he must find his humanness.

De Beaumont, on the other hand, was writing for well bred young ladies and in her tale, the emphasis is on Beauty needing to see past the Beast’s appearance. Terry Windling summarises in over the Journal of Mythic Arts

The emphasis shifts from the Beast’s need for transformation to the need of the heroine to change — she must learn to see beyond appearance and recognize the good man in the Beast. With this shift, we see the story altered from one of critique and rebellion to one of moral edification, aimed at younger and younger readers. (Terry Windling, Beauty and the Beast Old and New)

At the end of the day, I don’t want to have to tame a Beast. I should not have to tame a Beast. I would prefer of relationship based on equal respect and regard. If I have to tame him he can just clear off.